Friedrich Nietzsche, when discussing the character of his countrymen, observed that to be German was to endlessly question ‘what is German‘. Many attribute this sense of civic alienation to a combination of rapid industrialization, urban migration, and population explosion. The Germans were a people ‘becoming’ and ‘developing’, in the words of Nietzsche, like many or perhaps all nations today. Societies in the midst of change – real or imagined – find formerly bold, confident citizens questioning their national identity and its meaning. Extremist groups charge into this cultural void, first connecting the disaffected with one another – usually based on tribe, religion, or ethnicity- then connecting the group itself to some often mythic past.

Friedrich Nietzsche, when discussing the character of his countrymen, observed that to be German was to endlessly question ‘what is German‘. Many attribute this sense of civic alienation to a combination of rapid industrialization, urban migration, and population explosion. The Germans were a people ‘becoming’ and ‘developing’, in the words of Nietzsche, like many or perhaps all nations today. Societies in the midst of change – real or imagined – find formerly bold, confident citizens questioning their national identity and its meaning. Extremist groups charge into this cultural void, first connecting the disaffected with one another – usually based on tribe, religion, or ethnicity- then connecting the group itself to some often mythic past.

This use – and abuse – of history is not unique to extremists, but what distinguishes them from moderates is the way in which they deal with the nuances and contradictions of history. That which does not fit their model must be cleansed either through mass revision or outright destruction. Neither the Taliban, nor the Khmer Rouge, nor the Soviets could reconcile themselves with history before the ascents of their ‘religions’, so they set about ‘correcting’ it: the Taliban by blasting Buddhist statues with anti-aircraft and tank fire, then finally dynamiting them; the Khmer Rouge by beheading their Buddhas; and Stalin by removing rivals like Trotsky from the historical record completely, even going so far as to ban any works criticizing those that he disappeared. History to the extremist is not an instrument of instruction, but a tool to batter one’s opposition. This is happening in two seemingly very different places: Mali in West Africa; and in the United States.

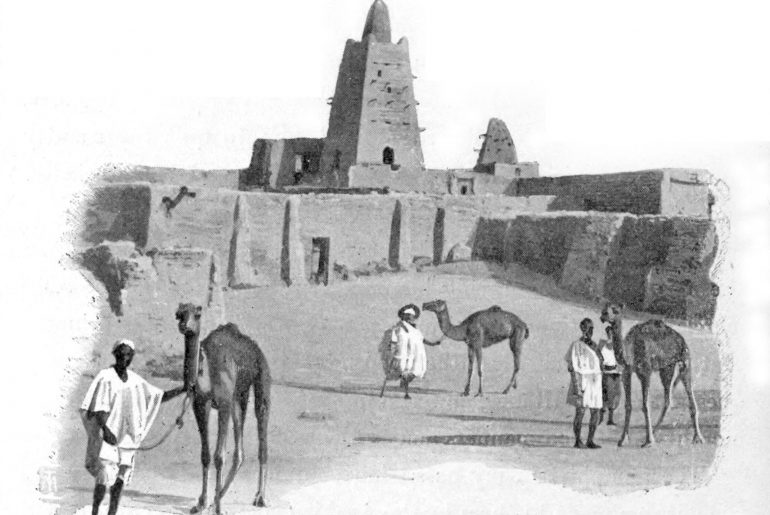

Civil war has split the West African nation of Mali in two, with a transition government headed by Prime Minister Chieck Diarra (former head of Microsoft Africa) in control in the South and something of coalition government in control of the North comprised of the three groups: National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad a secular group hoping to achieve freedom of religion and lifestyle; Ansar Din, a fundamentalist Islamic group; and AQIM an Al Qaeda splinter group. As is often the case with ‘coalition governments’ that incorporate religious extremists, the secular movement has been marginalized and Al Qaeda, and to a lesser extent Ansar Din, are in control of northern Mali – an area the size of France – and are implementing their version of Sharia Law  which demands beheadings, amputations and the destruction of pre-Islamic or forbidden art and literature, which is particularly troubling because the city of Timbuktu continues to yield manuscripts and artwork that are vital to our understanding of the history of Sub-Saharan Africa.

which demands beheadings, amputations and the destruction of pre-Islamic or forbidden art and literature, which is particularly troubling because the city of Timbuktu continues to yield manuscripts and artwork that are vital to our understanding of the history of Sub-Saharan Africa.

The history of Timbuktu presents Islamic extremists like Al Qaeda with a challenge. On the one hand, it is a testament to an era when Islamic nations were at the forefront of science, technology, medicine, astronomy, and literacy, but the version of Islam practiced in advanced societies in the ancient world tended to be more tolerant than that envisioned by modern jihadists. In Timbuktu, for example, Tuaregs often leave tokens for dead relatives at burial sites. They use charms and speak of desert spirits (djinn). They combine Islamic practices with local traditions. All of which suggests that tolerance might be a necessary pre-condition for a return to past glories, but that of course would mean moderating their stance and well… that’s not Al Qaeda’s way. Priceless artifacts along with texts and burial mounds have been destroyed in Timbuktu since the April of this year. The city’s history as a diverse center of learning offends the sensibilities of Al Qaeda more than Timbuktu’s history as a center of the slave trade. That history is a problem for extremists in another nation: the United States of America.

While right wing American activists warn of coming Sharia law and Muslims infiltrating the highest levels of government, they engage in their own  version of cleansing American history. Intellectuals on the political Right have argued for decades that public schools are instilling un-patriotic or un-American values in school children, using this charge as a pretext to attack sex education, global warming education, any mention of gays, evolution and of course what conservatives call ‘oppression studies’. This movement has gained momentum since 2009, with Arizona schools banning ‘ethnic studies’ and any textbooks in which ‘race, ethnicity and oppression are central themes’; Louisiana making it legal for public schools to teach creationism as science ; and Tennessee and Texas dealing a kind of ‘one-two punch’ to the history of American slavery, with the Tennessee Tea Party working to remove it from school books completely and Texas – more disturbingly in my view – voting to rename the slave trade the ‘Atlantic Triangular Trade’, a euphemism that would make any ‘gentleman’ of the Old South beam with pride.

version of cleansing American history. Intellectuals on the political Right have argued for decades that public schools are instilling un-patriotic or un-American values in school children, using this charge as a pretext to attack sex education, global warming education, any mention of gays, evolution and of course what conservatives call ‘oppression studies’. This movement has gained momentum since 2009, with Arizona schools banning ‘ethnic studies’ and any textbooks in which ‘race, ethnicity and oppression are central themes’; Louisiana making it legal for public schools to teach creationism as science ; and Tennessee and Texas dealing a kind of ‘one-two punch’ to the history of American slavery, with the Tennessee Tea Party working to remove it from school books completely and Texas – more disturbingly in my view – voting to rename the slave trade the ‘Atlantic Triangular Trade’, a euphemism that would make any ‘gentleman’ of the Old South beam with pride.

Slavery as an institution was endemic throughout recorded history having been endorsed and practiced by most groups in one form or another. The American innovation was to make it race-based and congenital, sort of like the color of one’s eyes or hair. To be born a slave was to die a slave and to bear slaves – not due to the usual reasons of war, conquests, or debts – but by virtue of being of African descent in the American South. The institution nearly divided our nation at its inception and helped cause a Civil War – America’s bloodiest war to date. Economists, historians, philosophers and others will debate the implications of slavery for centuries to come, but most thinking people will agree that its most important element was not the ocean that the ships sailed upon (Atlantic) or the geometric shape of the ships’ nautical paths (Triangular) or the precise economic label for the transactions (Trade). The defining feature was the slave – my ancestors and perhaps some of yours.

The return to speaking about slavery in euphemistic terms does several things simultaneously. It reclassifies the slave from a human being back to a commodity. It reaffirms the Old South’s image of slavery as a ‘peculiar institution’ devoid of its inherent brutality. And it diminishes both the tragedy of  slavery and the triumph of Emancipation and subsequent progress. Everyone does not view ‘progress’ in the same way as we all know. Many woke up the morning after the election of the first African-American president and reacted a bit like Richard Pryor’s ‘first man’, asking themselves ‘Where the fuck am I? And how do I get to… America?’ This alienation has been fuel for a succession of odd movements ranging from Birthers to Tea Party-ers, all of whom eager to take their country ‘back’, but not certain of where that ‘back’ is. Is it the 1950’s with its bigger government and higher taxes? Or the 1850’s with it’s fragmented, divided government? Or is it the 1750’s when there was no government at all? Regardless, this sentiment – or sentimentality – translates into real political power that we will have to contend with as America becomes ‘browner’, more interconnected and those who would like to live in a Norman Rockwell painting become increasingly alienated.

slavery and the triumph of Emancipation and subsequent progress. Everyone does not view ‘progress’ in the same way as we all know. Many woke up the morning after the election of the first African-American president and reacted a bit like Richard Pryor’s ‘first man’, asking themselves ‘Where the fuck am I? And how do I get to… America?’ This alienation has been fuel for a succession of odd movements ranging from Birthers to Tea Party-ers, all of whom eager to take their country ‘back’, but not certain of where that ‘back’ is. Is it the 1950’s with its bigger government and higher taxes? Or the 1850’s with it’s fragmented, divided government? Or is it the 1750’s when there was no government at all? Regardless, this sentiment – or sentimentality – translates into real political power that we will have to contend with as America becomes ‘browner’, more interconnected and those who would like to live in a Norman Rockwell painting become increasingly alienated.

Many argue that ‘he who controls the past controls the future’, which is true but first ‘he’ must control the present. The goal in Texas is the same as Timbuktu: to turn critique into blasphemy; honest inquiry into subversive prying; and history into a commodity that can be leveraged for political gain. Texas school board members even called Thomas Jefferson’s importance into question – not because of new discoveries or revelations – but because he advocated separation of church and state. History itself though, is not the ideal co-conspirator in this kind of farce which explains the orgies of destruction sometimes waged against it. The voice of history is as Freud describes that of reason ‘soft, but very persistent’. Even its enemies would be wise to listen.