“Django Unchained” leaves me in the odd position of contributing to a problem while I propose a solution to it. Django’s not a serious film about slavery or race or anything really and does not warrant the attention or the controversy that it has created. It’s both a blood-soaked, action-packed romp and a rescue revenge story. It’s also a kind of thought experiment akin to gun rep Larry Ward’s claim that if slaves had had guns they could have shot their way to freedom. Nothing about Django as an idea is offensive or inspired or controversial, but that seems to be a problem for Tarantino. Django’s lack of the kind of depth and complexity that spawns real debate seems to have spurred the filmmakers to manufacture dissent by manipulating the press and pundits, which explains Tarantino’s criticism of Roots, his use of “niggers” and his pretend outrage at critics who question his use of violence.

Django reminded me of my childhood – not a youth spent settling vendettas and escaping retribution, but one spent watching movies about settling vendettas and escaping retribution. Friday nights meant “five movies for the price of three”, so of the five at least one would be a violent, salacious b-movie that I managed to sneak into the pile by arguing that it “stars the guy from that other movie”, then urging my mother to the counter and out of the door.

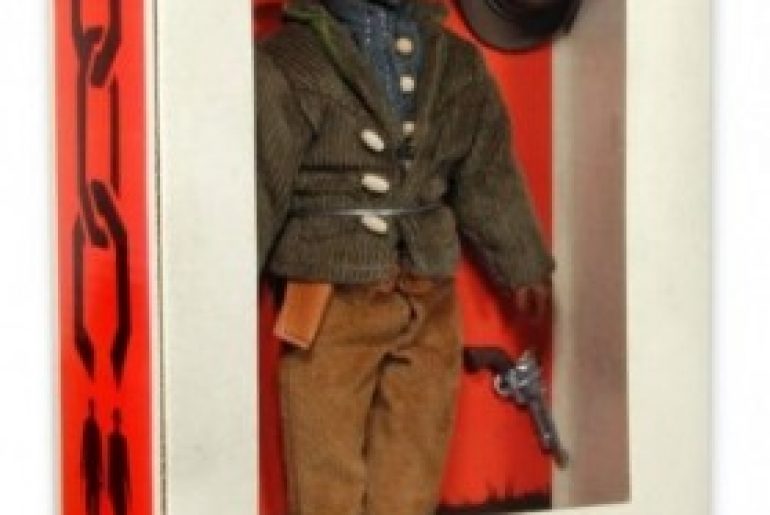

B-movies like Django are often set against an authentic backdrop and deal with relevant social issues with some limitations. Women’s prison movies touch on the corruption of the prison industrial complex ,when not tantalizing the audience with shower scenes and girl-on-girl action. Vigilante movies explore urban decay, when not demonizing cities, minorities, and liberals. Mutant animal attack movies with bees, piranhas, or tarantulas tackle the relationship between humans and their environment, when not fixated on creative ways to eviscerate, decapitate or devour the insides of some unwitting co-ed or pseudo tough guy. Django is absolutely a part of this tradition albeit with better acting, dialogue and promotion. Like most b-movies, the stakes of Django are very realistic, but the action is fantasy. The consequences of being caught for Django are like those of real slaves, but the way he evades capture and whips the bad guys is more Truck Turner than Nat Turner. Just to highlight my point, let’s look at a favorite b-movie of mine: The Evil that Men Do, starring Charles Bronson.

In The Evil…, Charles Bronson plays Holland – an assassin nearing retirement, but compelled to use his skills to track down a sadistic government official and torturer called Dr. Moloch or El Doctor. Moloch’s character is likely a fictionalized mix of Dr. Mengele, a Nazi degenerate scientist and Argentina’s Dr. Jorge Berges, aka Dr. Death, who melded science, sadism and commerce in ways that that Argentina is still trying to explain. The Evil…’s Dr. Moloch tortures and kills one of Charles Bronson’s friends, leading Bronson to mark him for death and the movie unfolds from there.

While El Doctor is ripped from the headlines of the day, Bronson’s character is a comic book action hero, albeit with Bronson’s own limitations as an actor and sixty year old man, who delivers with the wit, brutality, and panache we expect from that genre of movie. He guns down multiple adversaries then escapes unscathed. He spits pithy one-liners while his opponents mumble inane threats. In one of the movies most memorable scenes, a tough guy makes a rude pass at Bronson’s lady-friend and Bronson chokes him out with the heel of his boot while clutching the guy’s nuts for leverage.

As an audience, we of course know that none of this is realistic regardless of the movie’s backdrop. State repression was of course very real in Latin America in the 1970s and 1980s. Torture was common and US complicity is well-documented, but The Evil That Men Do, draws from that, but it is not about that. The reality of state repression is a plot device in The Evil… creating suspense for the viewer, while ensuring us that the main character will not be “disappeared”, or electrocuted to death, or thrown from a plane, or any of the things that actually happened to those who threatened the repressive regimes of the era. We know that Bronson will escape and us with him.

As an “A List” filmmaker the above simply will not do for Quentin Tarantino, but rather than do a movie that speaks for itself, Tarantino courts controversy claiming complete artistic license in one breath and a dedication to truth and authenticity in another. He has criticized Roots on the grounds that it ‘oversimplified slavery’. Jamie Foxx has argued that his character Django is ‘Kunta (Kinte) evolved’. Tarantino lashes out at critics who question his excess use of “nigger” and violence. He will tell the truth, he says, no matter how much his critics demand that he lie.

Tarantino’s critique of Roots is legitimate to an extent and would lead one to expect that, to combat Roots’ simplicity and sanitization, Taratino has made a movie that tells a story about slavery with both complexity and a dedication to realism and authenticity. Django Unchained is hardly that.

The movie is set in the late 1850s when slavery is being challenged on many fronts. John Brown has led two successful small-scale insurrections by 1858 before his infamous campaign at Harper’s Ferry. Fredrick Douglass is speaking so eloquently against slavery that even some abolitionists argue that he could not have been a slave – a charge he answers by showing the scars on his back. Joseph Wedemeyer, a German and colleague of Karl Marx, has started one of the nation’s first interracial – in word at least – labor organizations in 1853, The American Workers League.1. Many have come to the realization that the nation will not for long exist ‘half slave and half free’ and it is into this social tinderbox that Tarantino thrusts a German and an ex-slave armed with their guns, their wit, and some court documents.

The stakes of Django – like The Evil… – are real, so the villains that represent them have a whiff of authenticity. Calvin Candie, played by Leonardo Dicaprio, is a vain, ignorant, incestuous faux aristocrat completely befitting the Old South and consistent with some of slavery’s greatest defenders: men like John C. Calhoun, who married his first cousin; or James Henry Hammond who wrote openly about molesting four of his nieces. Blood thirst was common among slave owners. Southern Senator and slave owner, John Randolph, fought his first duel at eighteen, shooting a fellow debating society member over a disagreement about the pronunciation of a word. He threatened to shoot Senator Daniel Webster over sugar legislation. His plantation was called “Bizarre”2. Calvin Candie is perhaps tame by these standards and his Head House Nigger, played by Sam Jackson, is a hilarious mix of Uncle Ruckus and Uncle Remus, but the threat they represent is wholly authentic, while the actions our heroes use to oppose that threat are not.

Django, dressed like a pre-teen aristocrat, guns down two overseers in front of other slaves then walks away unscathed. He becomes a world-class killer in a matter of months mastering the handgun, the rifle, and holstering/unholstering tricks we have come to expect from cowboy action heroes. He guns down a house full of vigilantes, surrenders, then re-escapes from his new captors – this time armed with explosives. In each iteration, Django acquires new weapons, new accessories, and new skills: sunglasses, swagger, a hat-tip for female onlookers. By the end of the movie he has morphed into a demolitions expert and an honorary Isley Brother. None of this strikes me as authentic but rather choices: aesthetic, plot and other kinds of choices. The movie’s use of “nigger” is just one more choice, not a sign of artistic courage or of a dedication to authenticity.

Django does not improve on Roots. The violence of it is tame compared to the actual slave trade. And it does not need “niggers” to work as a movie anymore than it needs for the main character to suffer the gruesome fate that awaited many a black man uppity enough to wisecrack, shoot, or destroy the property of white men in the 1850s. If Django were torn to pieces like Nat Turner or caged and left to die like Toussaint L’Ouverture, then it would be a very different kind of movie, not because those scenes are too graphic, but because Django Unchained is ultimately a fantasy movie about escape: ours and his. That is the only “truth” about Django that Tarantino can defend.